Matthew Wong (1984-2019): A brilliant artist pained by depression

Canadian painter Matthew Wong, recognized internationally for his evocative works, had a brilliant career sparking critical acclaim.

By Lou Mo, 3rd August 2020.

In an age when art creation becomes increasingly versatile both in medium and expression, it takes courage and talent to establish oneself as a painter. Canadian prodigy Matthew Wong achieved global acclaim through his powerful and vibrant paintings. Unfortunately, his brilliance shone too short in this world. In 2019, the artist committed suicide in Edmonton, Alberta at the age of 35. Wong left a resounding legacy that continues to intrigue the art world. A look at his background and his work will help us understand Matthew Wong’s art and its enchanting qualities.

In an age when art creation becomes increasingly versatile both in medium and expression, it takes courage and talent to establish oneself as a painter. Canadian prodigy Matthew Wong achieved global acclaim through his powerful and vibrant paintings. Unfortunately, his brilliance shone too short in this world. In 2019, the artist committed suicide in Edmonton, Alberta at the age of 35. Wong left a resounding legacy that continues to intrigue the art world. A look at his background and his work will help us understand Matthew Wong’s art and its enchanting qualities.

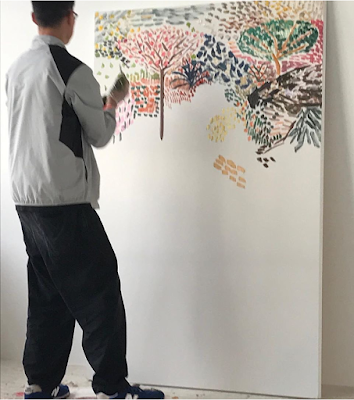

Matthew Wong started producing art in 2012, and he taught himself to paint and draw from scratch and adopted a rather gestural method. This makes what he had achieved in his very brief career as a painter all the more astounding. Matthew Wong’s style matured quickly. He started painting as a trial by chance as he found out during his graduate studies that photography was not the medium that could carry out what he wanted to express. Looking back to works later exhibited, what is also inspiring is the ease with which Matthew Wong was capable to capture different moods in creating artworks whose ambiance range from extreme tranquility to mystic rhythm.

Most of Wong’s large-scale works are landscape or still life paintings with a minimal hint of human presence. Wong stated in an interview that his works are spontaneous and intuitive, as he worked directly on compositions inspired by his experiences and imagination without making preparatory drawings. This immediate quality does transpire in his work all the while echoing some uncanny aspects of modern life such as solitude and melancholy.

Matthew Wong was born in Toronto in 1984, but he lived in two countries and two cultures. Between ages 7 to 15, Wong lived in Hong Kong before returning to Canada. He studied cultural anthropology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor before moving back to Hong Kong in 2007. There, he enrolled in the City University of Hong Kong’s MFA program specializing in photography. An avid reader, Matthew Wong was not only interested in reading about art, but he was also interested in literature and wrote poems regularly.

Art permeates the intellectual life of the artist who was constantly looking for ways to narrate his feelings, and Wong continued to practice photography and poetry even as he established painting as his main method of expression. As for painting as his medium of choice, the artist himself reflected eloquently, “at the center of my practice is exploring the materiality of paint and struggling to yield a surface that gives a sense of space and structure, however contradictory, that reaches a state of form I can live with.”

His name in Chinese, Chun Kit, includes two characters meaning handsome and outstanding, respectively. These qualities are equally true of his artworks, often signed in Chinese on the reverse. His art reflects this richness and diversity in his background, and one with an observant eye is prone to find in the painter a sensible and tranquil understanding of a huge array of artistic influences ranging from Paul Sérusier to Shitao, from Vincent van Gogh to Alex Katz.

Matthew Wong soaks up painterly possibilities like a sponge to churn out something that is his own, modern and pulled together. Often cited inspirations include Post-Impressionism, Nabi, and Fauvism. Equally present in Matthew Wong’s work is a quest to understand what could a painting be in today’s world, the artist’s experimentation went from colours, patterns, perspective, and dimensions to scale, drawing from an enormous corpus of knowledge. Sometimes, the painter called to Eastern references to resolve these issues playing hide and seek with the viewer’s eye, as Chinese literati painters would have done.

Social media has been an important tool for the artist’s creation and interaction with the larger artistic community. Wong had been active on Facebook, and his work attracted much attention and praise from well-known critics from Jerry Saltz and Roberta Smith to Eric Sutphin. The painter’s breakthrough moment came in 2018 with a solo show at New York’s Karma. Saltz commented that the show was “one of the most impressive solo New York debuts I’ve seen in a while.” Roberta Smith’s comment in the New York Times was even more touching and intimate, she thinks his work “was deeply nourishing: my life had been improved and I know other people who have had the same reaction. Such relatively unalloyed pleasure is almost as essential as food.”

Matthew Wong committed suicide at age 35, a shock and tragedy for the art world, devastated to see a star fall so quickly. It was shortly after he finished the works for a now-posthumous exhibition for Karma. By that time, he was already shown in a number of galleries in New York and Hong Kong, off to a very promising career. The show Blue features a series of paintings and works on paper, and the eponymous blue dominates these works. What is touching is the deeply resonant emotive quality of Wong’s work, so tender and pensive but in direct communion with the viewer. Wong’s mother, with whom he was very close, said that the artist “on the autism spectrum, had Tourette’s syndrome and had grappled with depression since childhood.”

'A dream', 2019.

In 2020, a small Untitled watercolor by Matthew Wong, dated 2018 and originally exhibited at Karma in New York that spring, was sold by Sotheby’s online as the opening lot of a contemporary art day sale. The hammer price went many times over its high estimate of US$ 15,000 by finally settling down on US$ 62,500. The work in question is a calm still life basked in vermillion tones, the colours saturated and dreamlike. A few persimmons lay on the right side beside a candle and a glimpse of a vase with flowers.

A couple of months later, another oil canvas painting titled Mood Room, also dated 2018 with the same provenance, achieved more than US$ 800,000 at Phillips New York’s evening sale. This fine and gorgeous interior scene encapsulates what modern painting has come to incarnate both in its exquisite style and the irresistible mood emanating from the room. Within the span of a few days, another reached the million-dollar status at Sotheby’s contemporary art evening sale. Wong is not uncalled for success. Understandingly so, his career was too short with few works available on the market for those who enjoy his art.

'Untitled' (persimmons, candle & vase) 2018.

'Mood room', 2018, Phillips.

Lou Mo; I graduated with BA in Art History from McGill University and later studied Chinese Art in the Asian Studies division of Paris' École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

'Morning landscape', 2017.

'Winter's end', 2019.

'See you on the other side', 2019.

Matthew Wong.

Monita Cheng, Matthew's mother.

I was struck by the different techniques that distinguish these paintings from the ones Wong had shown in the same space a little more than a year ago. In “Blue Rain” (2018), he depicts a blue path leading through a field of white flowers to a house abutting a forest of tall, straight trees. Part of a vast full moon dips down into the painting’s top edge. What differentiates this from his earlier paintings is the additional layer of diagonal brushstrokes indicating rain. As in “Blue Night” and “Path to the Sea,” there is something meaningful about the incongruity. In “Blue Rain,” it seems to be raining torrentially on the night of a full moon. The moon, directly above the house, is like a beacon guiding us to shelter. The rain, however, becomes a curtain of marks separating the viewer from the house.

Matthew Wong.

Monita Cheng, Matthew's mother.

Matthew Wong: Kind of Blue

It seems that Wong was in touch with his deepest feelings and they came through in all of his art; this is what makes him special.

John Yau, 7 December 2019

Matthew Wong, “Look, the moon” (2019), oil on canvas, 70 × 60 inches (all images courtesy of Karma, New York)

Matthew Wong’s career was all too brief, leaving those of us who were enthralled — as I was — by his debut show at Karma (March 22-April 29, 2018) wondering what he might have accomplished had he lived longer. After all, this was the work of a self-taught painter who began painting in 2012, shortly after graduating in Hong Kong with an MFA in photography. However, not long after he completed the work that comprises his current exhibition, Matthew Wong: Blue at Karma (November 8, 2019–January 5, 2020), he committed suicide at the age of 35. Although it is hard to separate the paintings and works on paper from this overshadowing fact, I think it is important to try.

Fifteen paintings are spread throughout the two galleries, office, and front window of the large exhibition space, while eleven small works on paper, done in gouache and watercolour, are in the smaller storefront gallery a few doors away. As the exhibition title suggests, the colour blue dominates almost all of the paintings and works on paper. Wong’s subjects are traditional: landscape and still life. This is how I described the paintings in his first exhibition at Karma:

Wong makes myriad lines, dots, daubs, and short, lush brushstrokes, eventually arriving at an imaginary landscape that tilts away from the picture plane at an odd angle. A painterly cartographer, Wong literally feels his way across the landscape, dot by dot, paint stroke by paint stroke.

While this method of working is true of a number of paintings, especially in the front gallery space, the paintings in the smaller back gallery show that Wong had broadened his approach to applying paint to the surface — perhaps as a result of using gouache and watercolour.

In “Blue Night” (2018), which measures 60 by 48 inches, an oversized pink tulip sits in a large glass half-filled with water dotted with air bubbles. The flower and glass are in a dark blue room, sitting on a light blue surface. Behind them we see a closed door on the left and a window on the right, in the corner. Outside the window, beneath a curving band of deep blue sky, there is a tree with orange leaves, rendered with fat dots of paint. By the table on which the glass sits are the horizontal blue slats of wooden chair nearly submerged in the painting’s dark blue light.

The water glass and lone flower are too big in relation to the rest of the things in the room (the door, chair, and window). They dominate the space, demanding the viewer’s attention. At the same time, there is something tender and vulnerable about the long, thin-stemmed flower standing erect in a big glass. Is the rim of the glass holding up the flower or is it magically standing on its own? The longer we look at what might at first appear to be a simple composition the more we see.

This is what makes Wong special: it seems that he was in touch with his deepest feelings and they came through in all of his art. And feelings, as they say, can be messy. For this reason it is reductive to see his work through the single lens of his suicide. We owe Wong and his work more than that. This is why I decided not to go to any other exhibitions on the day I saw this show.

“Untitled” (2019), gouache on paper, 12 × 9 inches

In “Path to the Sea” (2019), a charcoal gray path emerges from the middle of the painting’s bottom edge, rising and diminishing until it ends about three-quarters of the way up the painting’s surface. Above it is an oval — a clearing — made of three horizontal bands in various hues of blue, denoting the sky, ocean, and land. On both sides of the sinuous path Wong painted trees, leaves, foliage and fauna, using a vocabulary of full dots, dashes, and brushstroke lines. White and black paint accent the thick forest and indicate moonlight and shadows.

Wong’s works hint that he wanted a direct rapport with the viewer; often, simple gestures, as in his placement of the path, pull us into the painting and raise our attention up the painting’s surface. In fact, we might not initially notice the figure — whose head and back are seen from behind — entering into the painting from the bottom left edge. I felt a shiver of displacement pass through me as I took in the whole scene. Wong has located his viewer behind this solitary figure, who is walking through a forest at night to reach the sea. The forest is crowded with marks while the sea and sky are relatively empty, with five stars in the uppermost band. Who is this person that we seem to be walking behind and accompanying?

In his earlier paintings Wong tended to cover the surface with myriad marks, from daubs and dashes to lines of varying lengths and widths; grouped together, they articulate a landscape made up of simple and direct paint application. There was something honest and innocent in this. The result was optical and dreamlike.

“Blue Rain” (2018), oil on canvas, 72 × 48 inches

I was struck by the different techniques that distinguish these paintings from the ones Wong had shown in the same space a little more than a year ago. In “Blue Rain” (2018), he depicts a blue path leading through a field of white flowers to a house abutting a forest of tall, straight trees. Part of a vast full moon dips down into the painting’s top edge. What differentiates this from his earlier paintings is the additional layer of diagonal brushstrokes indicating rain. As in “Blue Night” and “Path to the Sea,” there is something meaningful about the incongruity. In “Blue Rain,” it seems to be raining torrentially on the night of a full moon. The moon, directly above the house, is like a beacon guiding us to shelter. The rain, however, becomes a curtain of marks separating the viewer from the house.

In “Look, the Moon” (2019), Wong waited until the oil paint was dry and sticky, rather than smooth and creamy, before applying it to the surface — instead of distinct brushstrokes and marks, the surface is textured and seems gummy. This deliberate move evokes a forest full of pine trees partly obscuring the moon, which is framed by two leafless birch trees.

In these largely unpopulated paintings, Wong invited the viewer to be a solitary observer or sojourner. He never indicated what awaits us at the end of our journey. He seamlessly integrated contradictions into his works so that they reveal themselves slowly. Wong did so much in a short period — around seven years — I don’t think a sense of loss will ever leave me when I think about him or look at his work.

No comments:

Post a Comment